“Sir,” replied Julien, “I am troubled, embarrassed, wearing these new clothes; a poor peasant like myself has never worn anything more than a jacket. With your permission, I’ll close myself in my room.”

Stendhal, The Red and the Black, Part One, Chapter Six, 1830

Man is a textile animal.

If young Julien Sorel at the beginning of Stendhal’s The Red and the Black is so stiff in the clothes he wears, it is because he is weighed down by the role he has just accepted, that of tutor. His clerical garments have made him a priest; the technical object that is the cassock seems to make the man of the cloth.

Yet it is endlessly repeated that the habit does not make the monk, implying that the habit would in fact transform the man who wears it to the point of making him a priest. While it is clear that imposture can never be compensated for by any garment, Julien Sorel will learn this lesson himself: what we wear conveys a message.

Clothing, in this sense, carries a double dimension. The tailored, technical object coexists with the message, the aura, the sartorial intent expressed by the wearer. Clothing is a political, social, and economic tool, a reflection of a history and a heritage we lay claim to when we get dressed.

We must therefore present a historical overview of clothing, tracing its evolution through the political, economic, and industrial choices of successive eras, in order to understand what legacy we inherit when we adopt and perpetuate codes that are, in some cases, centuries old.

Old Regime Power Through Clothing

When Hyacinthe Rigaud painted the Sun King in his coronation robes in 1701, he was first and foremost depicting a political figure dressed in ceremonial attire. The king, shown from a low angle, is portrayed from head to toe in the full splendor of Versailles at the time. Tight white stockings, a blue mantle strewn with fleurs-de-lis, an ermine lining, scepter, hand of justice, Charlemagne’s sword, and a crown delicately placed on a cushion. Every element carries a powerful symbolic meaning.

For the king, the point was to show that he wielded power even through what he wore. He was the state, and what he wore was as much an embodiment of the state as he was himself.

A paragon of Old Regime opulence, Louis XIV epitomizes the total political costume. This is why the revolutionaries of 1789 would attempt to break away from this symbolism by adopting a form of sobriety, though not one entirely of the people.

Early 19th-Century Bourgeois Clothing

Inspired by the revolutionaries, the English bourgeoisie gradually adopted a more sober style. The goal was to become a bourgeois, capitalist, and powerful Third Estate that the people would have no interest in overthrowing. It is in this period that the modern suit begins to emerge.

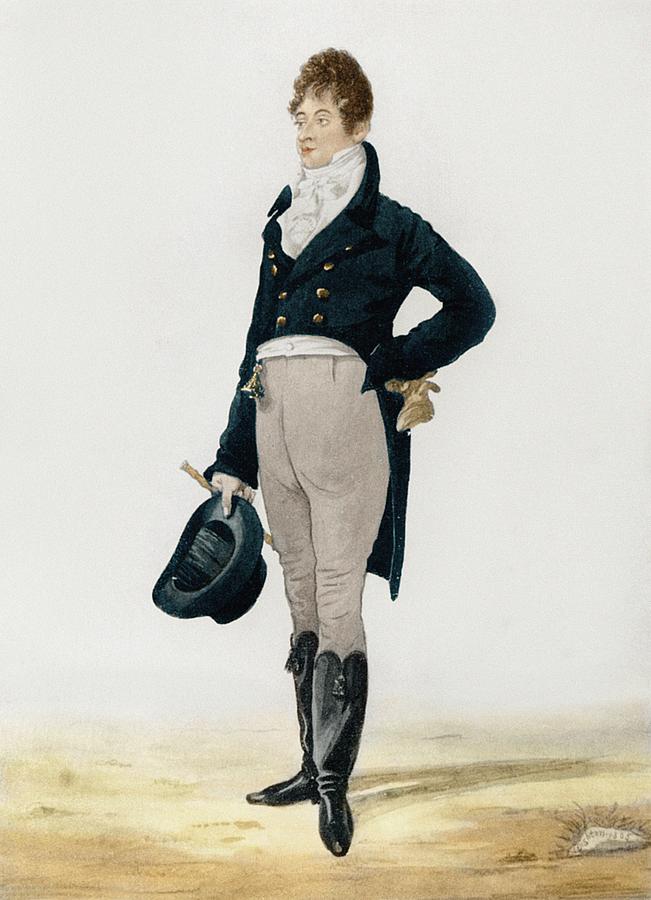

The Englishman Beau Brummell, often considered the first true dandy, is a prime example of this early 19th-century bourgeois dress. Wearing a fitted jacket, a perfectly tied white cravat, a double-breasted coat with gilt buttons, and high-waisted, simply cut trousers, Brummell embodied the rejection of the embroidered, ostentatious garments of the Ancien Régime. He imposed a clean, minimalist, and structured silhouette, elements that still echo in today’s finest business suits.

Brummell built his public persona around strict stylistic principles (discipline in fabrics, rigor in color, discreet elegance) establishing a standard of refinement without ostentation : the first stirrings of English understatement. The shift from the embroidered justaucorps to the long trouser, simple wool cloth, and frock coat marked a decisive turn toward attire imbued with bourgeois morality.

The flamboyant aristocratic style faded in favor of clothing that was more functional and modest. This movement, known as The Great Masculine Renunciation, heralded the advent of the three-piece suit.

Brummell’s understated style spread through the British elite. Buttons, cravat, starched shirt, coat line, well-cut waistcoat—these elements became references that French tailors and elites soon embraced, contributing to the rise of a uniform and impersonal style. Even as king, Louis-Philippe, King of the French, had himself portrayed in bourgeois attire, far removed from the Jupiterian figure of the Bourbons.

This new mode of dress was made accessible to the wider bourgeois strata through the rise of specialized tailors offering fitted cuts, varied fabrics, and starched shirts. The artisan tailor became a key actor in the standardization of fashionable clothing.

1850–1900: The Era of Self-Assertion Through Clothing

The 19th century was a bourgeois century, a time when social, political, and economic circles solidified, and where belonging to a given social sphere was signaled through clothing. A stroll through the Musée d’Orsay will lead you to James Tissot’s The Circle of the Rue Royale (1866). The painting depicts the circle gathered on a terrace of the Tuileries : twelve aristocrats in frock coats, cravats, and sober waistcoats, seated or standing in carefully studied poses. The painting captures the moment when the male suit definitively became a marker of a discreet, closed elite with ambitions of power.

Each man wears a black or gray frock coat, knee-length, with a fitted waist and understated collar. This formal coat, which appeared around 1820, dominated bourgeois public life until the 1890s. It reflected the moral rigor and social hierarchy of the elite.

It should be remembered that at this time, the bourgeoisie had only just secured its place in political power. The goal was to demonstrate that they were worthy of the public responsibilities that monarchists still contested. The relative austerity and uniformity of their attire was intended precisely to reassure detractors : they would govern because they could, and because they had the stature to do so.

The painting also hints at the coming evolution of men’s dress : some lighter waistcoats and slightly shorter cuts foreshadow the emergence of the urban lounge suit. This three-piece suit, more functional and city-oriented, became the standard for informal daily wear in the 1890s.

The Golden Age of the Suit (1900–1945)

Little by little, the suit found its place. The Industrial Revolution also struck the textile world, and the automation of garment production led to greater standardization in urban wardrobes. Membership in an urban population was claimed by a more modest city-dwelling class, which adopted the codes of the era’s high bourgeoisie. With war came a time of sobriety and mourning : colors grew darker, cuts became straighter, and outfits more austere. Painter Tamara de Lempicka gives us a vivid illustration of this interwar austerity in her 1928 portrait of her alter ego, Mr. Thadeus Lempicki.

He wears a dark double-breasted overcoat and a light scarf. Hat in hand, he embodies the masculine elite of the 1920s–30s ; confidence, distinction, and discreet ostentation. The Art Deco geometry of the painting mirrors the architecture of the modern cities visible in the background. Politically, the image conveys the stability of institutions even in times of war, and by extension, the private world of banks and corporations. The wide-lapelled double-breasted coat and light scarf give the silhouette a powerful structure, symbolizing an urban man secure in his social standing, even through a world war (1914) or the stock market crash (Black Thursday, 1929). In the first half of the 20th century, the coordinated suit (jacket, waistcoat, trousers) became the universal uniform of the educated classes, while long overcoats accompanied city winters.

This aesthetic would later be seen in Hollywood, epitomized by Cary Grant and Fred Astaire, both trained in this school of style.

The Suit as Uniform? (1945–1980)

After 1945, the men’s suit became the universal uniform of urban modernity. It was no longer merely a sign of distinction; it reflected the standardization of a capitalist, consumerist society. Duane Hanson’s hyperrealist sculpture Executive (1971), depicting a weary man in a gray suit, perfectly crystallizes this transformation.

After 1945, the dark three‑piece suit established itself as the uniform of white‑collar workers in an era of economic growth and increasing bureaucratization. In contrast, the Victorian heritage and the flourishes of dandyism disappeared: the masculine ideal became sober, discreet, and interchangeable, embodying “respectability” rather than individuality.

The suit remained tailored, with narrow‑lapel jackets and tapered trousers, often accompanied by accessories such as a hat or a slim tie.

Men wore the corporate suit to take their place as agents of business or government.

Cultural liberation led to experiments : flared trousers, brighter colors, longer jackets, and wider lapels. Yet even in these bold variations, the suit remained the attire of the working world.

Well-Dressed Cinema

The turn of the millennium and the emerging post‑Soviet world order began to take shape as early as the 1980s. Triumphant Western powers, the financialization of the economy, and the overwhelming influence of the United States turned the suit into a true cultural emblem.

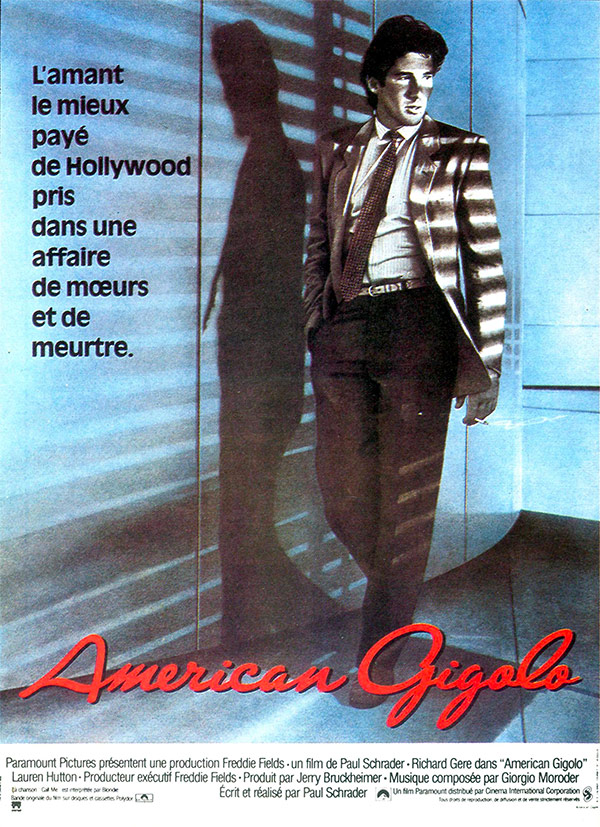

In this regard, the 1980 American Gigolo poster featuring Richard Gere offers an intriguing example.

The actor is shown in a light, fluid, almost sensual suit. The suit is no longer merely a professional uniform : it becomes an object of desire, tied to seduction, power, and the male body. This cinema reflects a societal transformation: financial success and hedonism merge. The sexy man is the one who eroticizes professional codes. Subversion is displayed, intentional, and desirable.

In the real world, the figure of the yuppie (young urban professional) embodies this fusion of business and style. Wide‑shouldered double‑breasted suits, pastel shirts, and flashy ties : the 1980s man flaunts his success. Wall Street, the City, and other financial centers impose this look as a visible sign of economic dominance. Films like Wall Street (1987) and Working Girl (1988) immortalize this conquering silhouette on screen.

Yet behind the glamour, the suit becomes even more standardized. The 1990s mark the triumph of global ready‑to‑wear. Corporate suits dress the world, creating cultural homogenization. The suit becomes both more accessible and more codified: gray, navy, or black, with straight cuts, structured shoulders, and fluid trousers.

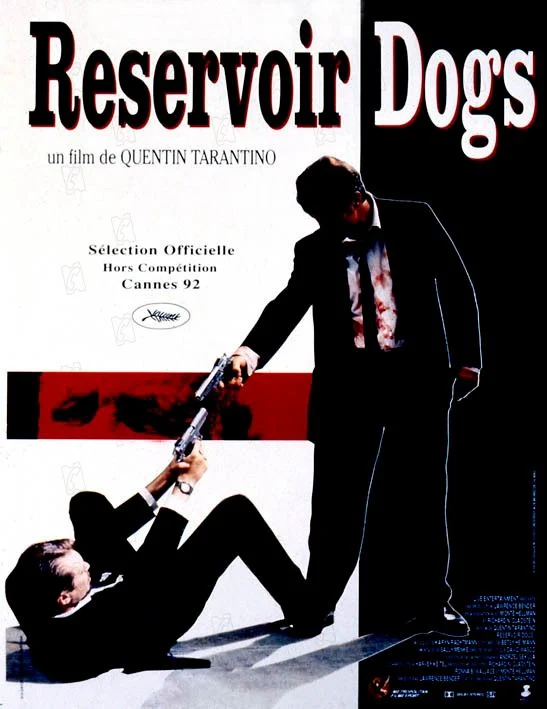

In popular culture, it turns into a narrative object. Tarantino makes it a visual signature with the black suits of Reservoir Dogs (1992). Men’s magazines and advertisements multiply images of suited men, selling less a garment than a promise ; that of power and control.

On the eve of the 2000s, the suit had become an icon. At once a corporate uniform and a cinematic symbol, it embodied a globalized urban modernity, paving the way for the accessory‑suit and the post‑formal aesthetic that would soon emerge.

The Power Suit Today and Tomorrow

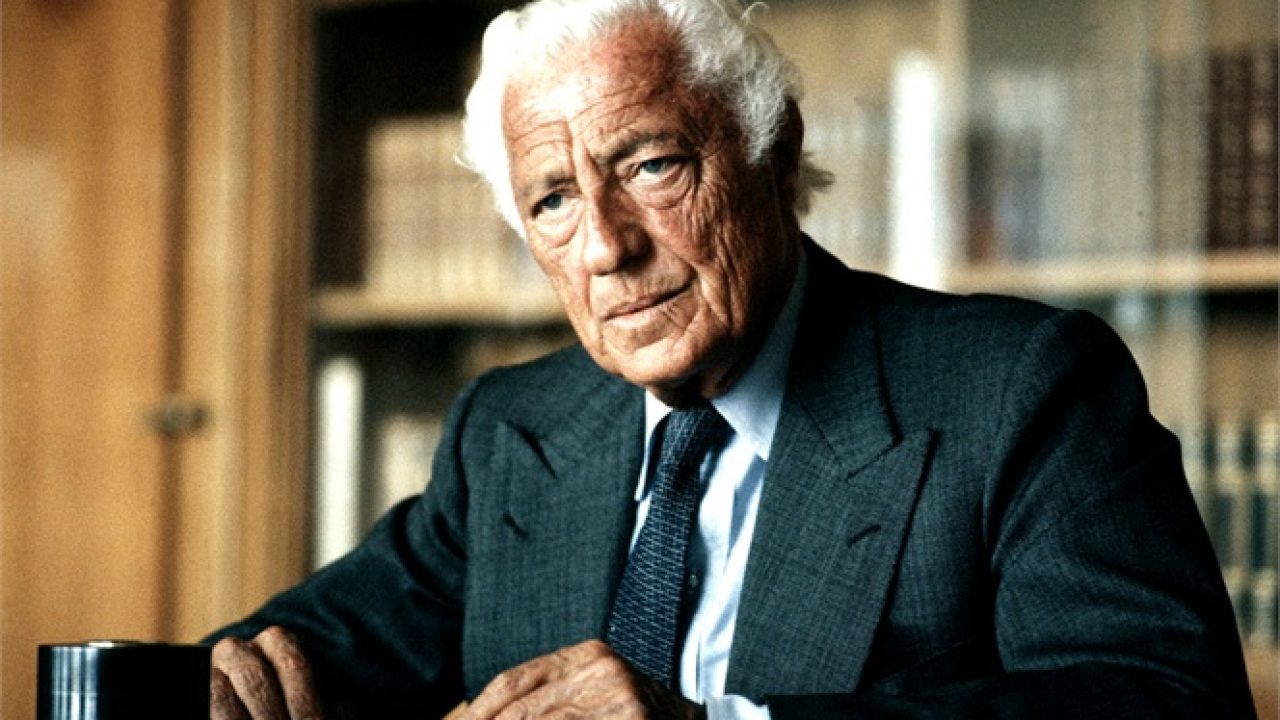

Far from being relegated to the closet, the suit has experienced a true revival since the 2010s, driven by the convergence of social media, craftsmanship, and a new generation of informed enthusiasts. Carried by the “sarto,” or sartorial movement (from the Latin sartor, meaning tailor), it has returned as a garment of style and passion rather than just an office uniform. Figures like Hugo Jacomet, with his Parisian Gentleman platform, have popularized the idea that a well‑cut suit is above all an expression of self, rooted in historic craftsmanship. His sartorial approach has entered the mainstream, with everyone seemingly embracing their own version.

On Instagram and TikTok, the sartorial community shares outfits, fittings, and technical insights, helping to democratize tailoring culture for a connected generation.

Hugo Jacomet wearing a Blandin & Delloye suit

Blandin & Delloye, Heirs and Ambassadors of the Modern Suit

Choosing a Blandin & Delloye suit means reconnecting with the history of menswear while firmly anchoring it in the present. Each piece is designed as a synthesis : contemporary cut, respect for classic codes, and true tailoring expertise. In their showrooms, from Paris to Ottawa, the client experience becomes a moment of transmission—selecting fabrics, shaping lapels, making precise adjustments, and personalizing linings or buttons.

In a world where the corporate uniform is giving way to personal style, Blandin & Delloye embodies the return to a meaningful suit, designed to last and tell a story. More than a garment, it is a signature.

The suit of tomorrow seems destined for a double life. On one hand, it will remain a garment of distinction for formal events and lovers of classic style; on the other, it will blend into more hybrid, casual uses, incorporating flexible fabrics, sneakers, or unexpected accessories.

The suit will not disappear for it will continue, as always, to adapt to the shifts in society and to the ways men wish to tell their story through clothing.